Increasing tongue- and lip-tie diagnoses are drawing scrutiny from Johns Hopkins doctors.

HeadWay Winter 2018

Several years ago, Johns Hopkins pediatric otolaryngologist–head and neck surgeon Jonathan Walsh noticed a trend: More and more infant patients were being referred to his practice for ankyloglossia, colloquially known as tongue-tie. These abnormal attachments of the lingual frenum can restrict the tongue’s movement, potentially hampering the complex and coordinated interactions between mother and baby necessary for successful breastfeeding.

In a relatively recent culture where “breast is best,” increasing breastfeeding rates in the U.S., it makes sense that more babies might be diagnosed with breastfeeding problems that might have been overlooked in bottle-feeders. But, is tongue-tie being overdiagnosed? And are the procedures used to remedy this problem—such as in-office clipping or laser frenetomy—always necessary?

In a relatively recent culture where “breast is best,” increasing breastfeeding rates in the U.S., it makes sense that more babies might be diagnosed with breastfeeding problems that might have been overlooked in bottle-feeders. But, is tongue-tie being overdiagnosed? And are the procedures used to remedy this problem—such as in-office clipping or laser frenetomy—always necessary?

Walsh and his Hopkins colleagues who evaluate and treat ankyloglossia and the related condition known as lip-tie, including David Tunkel, Emily Boss, and Margaret Skinner, decided to investigate this problem. In a recent paper authored by Walsh, Tunkel and Boss, the researchers put numbers to the tongue-tie diagnosis trend.

Using a national database with discharge information on millions of patients from thousands of American hospitals, the researchers searched for billing codes related to ankyloglossia from 1997 to 2012. Their search turned up steady increases over the years, from a mere 3,934 cases diagnosed in 1997 to nearly 33,000 diagnosed in 2012. Similarly, frenotomy increased with 1279 procedures in 1997 to more than 12,000 in 2012.

Although it’s clear these rates have increased substantially over the years, it’s unclear exactly why. Increased rates of breastfeeding are likely a factor, Walsh says, but data from their recent study and others have shown that ankyloglossia is more frequently diagnosed in the babies of first-time parents who are privately insured and in relatively high-income areas, suggesting that societal expectation and health disparities could be factors.

To get more insight on tongue-tie diagnosis and treatment decisions, Walsh and his colleagues have embarked on a study that’s examining social media and open blogs to analyze emerging trends on what parents are expressing about this condition. They’re also analyzing the available web-based information on tongue-tie to determine whether the resources that parents often turn to—such as WebMD or eMedicineHealth—adhere to evidence-based medicine and recommended reading levels for information geared toward nonexperts.

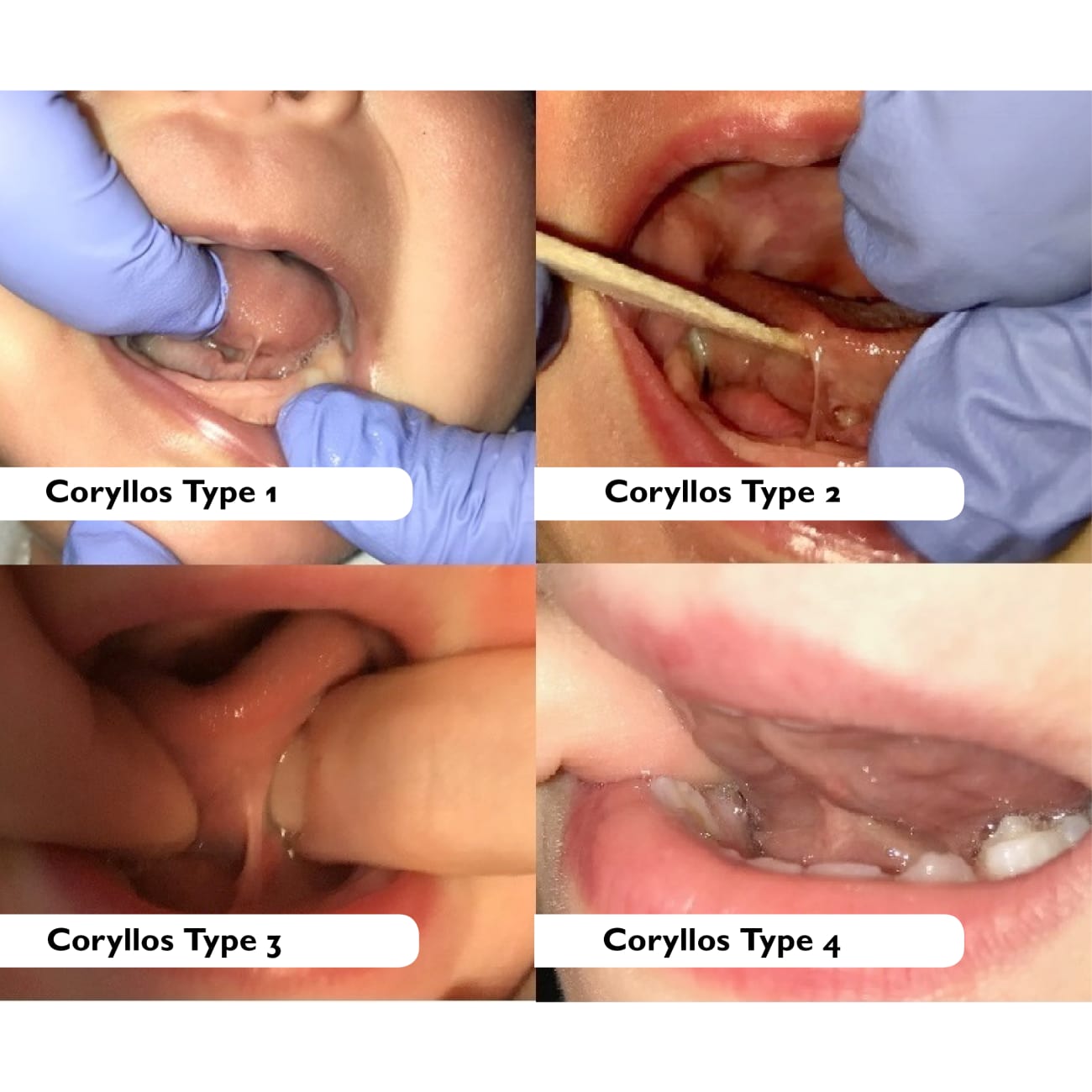

Lastly, Walsh points out that a lingering issue with both tongue- and lip-tie is that what constitutes a real pathology deserving treatment is unknown—there’s a wide variation of lingual and maxillary frenum anatomy, and it’s what’s in the range of normal. To help answer this question, he and his colleagues are conducting an ongoing study of lip-ties that involves taking photos of the maxillary frenum of every infant whose parents consent in Johns Hopkins’ healthy newborn nursery. Using image analysis, they’re gathering information on the frenum length, attachment, morphology and other clinical characteristics—including whether the baby has difficulty breastfeeding—to determine what constitutes a problem that needs treating.

“Until we figure out how best to diagnose which children are really having problems, we’ll be doing procedures on many more children than will be helped,” Walsh says. “We’re hoping to clarify which children will truly benefit from these interventions.”

To refer a patient, call 443-997-6467