November 5, 2018

Charles Rockstroh says he had it all. Then major depression took over, rendering him homeless and unable to work. He lived with relatives until they could no longer house him.

“I went from ER to ER, just to have a place to stay,” Rockstroh says.

Then he learned about Creative Alternatives. For 25 years, clinicians at this community psychiatry program, funded by the state and administered by Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in efforts to keep people with major mental illnesses out of psychiatric hospitals, have worked tirelessly to provide mental health treatment and rehabilitative living skills to its members.

About two years ago, a program representative came to Rockstroh’s father’s apartment to meet him. Impressed that Creative Alternatives would pay his rent until he found a place, he enrolled, taking advantage of individual and cognitive behavior therapy services. Now he lives with a girlfriend and holds a steady job in merchandising at a Home Depot. “I feel better about myself,” he says.

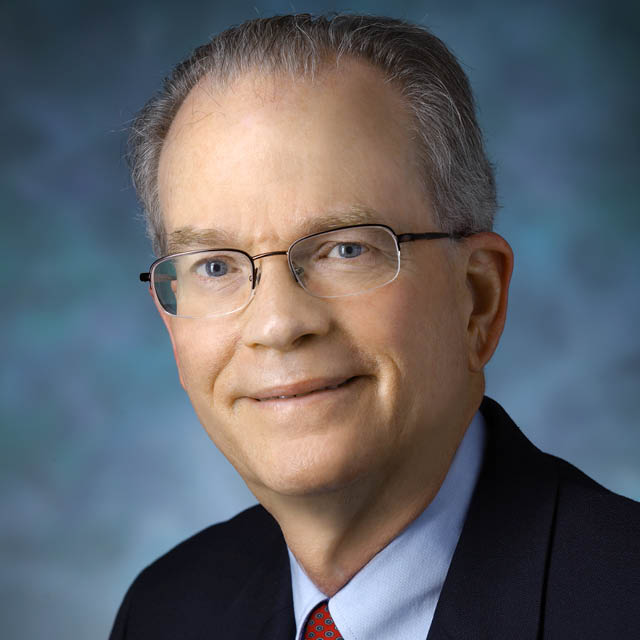

“The beauty of this program is we’re able to help people with their lives in so many ways that can ultimately benefit their mental health problems,” says psychiatrist David Neubauer, who has been with the program for about 20 years. Beyond mental health services, staff coordinators help members find housing, receive benefits such as Social Security or medical assistance, return to work or school, and get to doctors' appointments for co-occurring conditions. At a drop-in center on the Baltimore City’s east side, members participate in men’s or women’s support groups, take yoga classes, enroll in substance abuse treatment and learn to develop wellness recovery action plans.

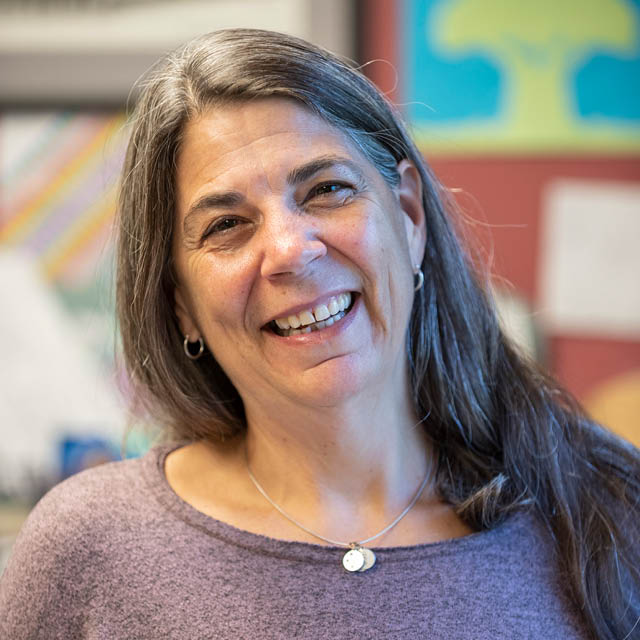

“What makes us so successful are the relationships that we build with the members,” says nurse and program manager Sheila Goldscheider. Beyond medical management, she says, “It’s about giving people meaningful roles,” and asking what their dreams were before becoming ill. Personal service coordinators dedicate their time to just 10 members each. The program also plans social outings such as a crab feast, fishing trips and Orioles games. An annual banquet honors members for staying sober, maintaining good relationships with family, or working.

Members average less than one hospital day per patient per year, says Goldscheider. About 10 percent are employed, and 65 percent live independently.

“Creative Alternatives is the best,” adds member Adrian Smith. “Some people say, ‘I don’t know what I would do without it.’”

Bolstering Emotional Support

The Department of Psychiatry offers additional wraparound services for patients. As one option, it is employing “telepsychiatry” appointments for adults with major mental illness who receive psychiatric management at home or in community settings through the Costar Assertive Community Treatment program. If a nurse or case manager observes an urgent situation, such as a patient not taking his or her medication, they can quickly alert the person’s psychiatrist and arrange a videoconference appointment on an iPad. While psychiatrists see all patients at least once a month, this provides a supplemental option for pressing issues, says Bernadette Cullen, director of community psychiatry.

The division is also studying automated text messages to help prevent relapse in patients with schizophrenia. In a research project funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, 28 of 40 patients who were enrolled in a randomized controlled trial receive daily text messages alerting them to one of five early warning signs of relapse, in addition to inspirational quotes and reminders to take medications. While the trial is ongoing, most patients receiving the text messages are responding, Cullen says.