Johns Hopkins Orthopaedic Surgery

February 3, 2014

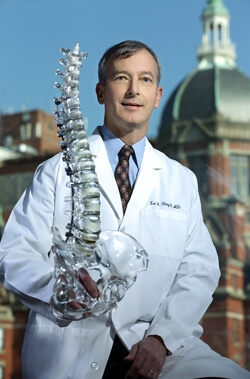

Orthopaedic spine surgeon Lee Riley has seen his share of both ends of the spectrum, but the condition that gives him the most pause is chin-on-chest deformity, the type of cervical kyphosis in which a patient’s chin has literally dropped to the chest.

Also called dropped head syndrome or head ptosis, the severe muscle weakness in the back of the neck that causes the condition can come on suddenly or be preceded by some neck pain.

“Maybe you can lift your head back up, but often it’s only temporary,” says Riley. “In the most severe cases, your body and your brain want your chin to go back to your chest. So, once your head has dropped, it’s going to stay there.”

Riley sees the condition most often in Parkinson’s patients, but it also can happen in people who’ve had strokes, head and neck cancer, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or who have a diagnosis like ankylosing spondylitis.

When the deformity is severe with chronic pain or accompanied by neurological problems because of pressure on the spinal cord, the need for surgery becomes less of an option and more of a requirement.

The procedure, which can take up to 10 hours, usually involves spinal fusion with segmental instrumentation. And, it often combines two surgeries within the same operation: the first to the front of the neck to release cervical contractions, and the second to the back of the neck to fuse the spine and prevent the condition from recurring.

“We have to be able to do this over an area long enough so that the neck can be held in place, but short enough to preserve function,” Riley explains. “From a numbers perspective, we’re usually working on the area between C2 and T3 or T4.”

While the technology has improved over the last decade and there’s a better understanding of chin-on-chest deformities and how to correct them surgically, Riley says there are still many people who won’t know there’s something you can do about it.

“It’s rare in the big picture of cervical and spinal deformities,” he says. “But, it’s life-altering once you’ve had it corrected. Patients should know that the procedure is available to them.”