August 13, 2019

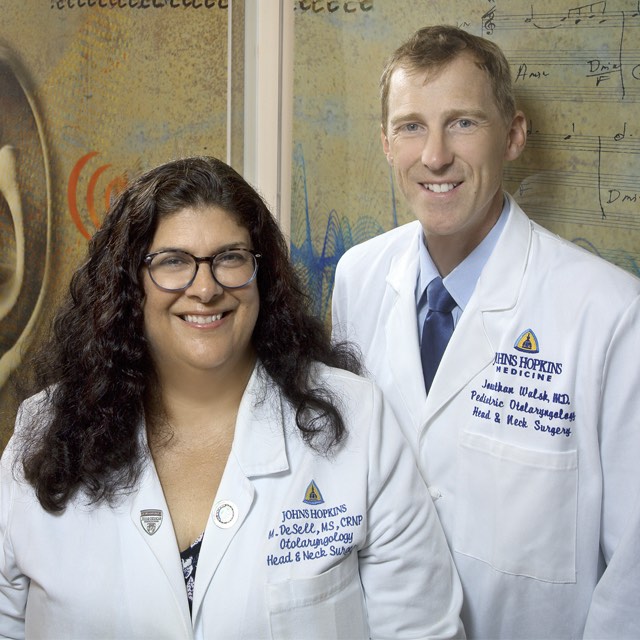

Johns Hopkins Pediatric nurse practitioner Nina DeSell has seen firsthand the consequences of delays in follow-up testing for infants who fail their initial newborn hearing screening. They include delays in diagnosis, treatment, and language and speech development for these young patients.

“When I first started here, I saw an 18-month-old from an inner city family who had so much trouble getting an appointment to test her hearing,” says DeSell. “She ended up being profoundly deaf and needing a cochlear implant at age 3, which we encourage the first year.”

While Maryland, like most states, requires a hearing screening before a newborn leaves the hospital, when those who fail have follow-up testing varies for multiple reasons. Sometimes, for example, the results of the initial screening are ambiguous, or hospital staff members do not clearly explain them. Too often, notes pediatric otolaryngologist Jonathan Walsh, the in-depth discussion that should take place does not happen.

“We know from studies that parents often don’t even know the results of the newborn hearing test. It’s not always clearly explained,” says Walsh. “In general, for most parents, it’s not completely obvious whether their child passed or not.”

To further complicate matters, many hospitals contract out follow-up confirmatory screenings and more advanced tests, leaving parents with a list of providers and phone numbers they can call at their leisure over the next two months. Consequently, many parents feel ambivalent about the urgency or need for retesting. But time is of the essence, DeSell and Walsh stress, both regarding speech and language development and detection of related hearing-loss issues such as cytomegalovirus that require early treatment. They and audiologist Alicia White developed the Infant Hearing Early Access and Rapid Diagnostic Detection (iHeardd) Clinic for newborns who fail their initial screening.

“We are trying to create access that is easy and streamlined, in which any hospital in the state could call this number and have an appointment for the confirmatory tests that are needed with our providers in this clinic,” says Walsh. “If the baby passes the test, great, they can still meet with our nurse practitioner and talk about what that means. If the child fails, the parents during that visit get a medical explanation of what it means and what happens next. If the child does have hearing loss, we can get resources to the family early on instead of three months later when the child has had hearing loss since birth.”

At iHeardd, infants undergo a comprehensive auditory brainstem response (ABR) hearing test. Unlike the initial hospital screening, which measures the baby’s auditory responses and issues a pass or fail score, the ABR test uses brain waves to determine whether hearing loss is conductive or neural. This more advanced test works well for young babies under 4 or 5 months of age who tend to sleep well and remain still during the test. Those 6 months or older and less prone to sitting still generally have to be tested under anesthesia, another reason for parents to seek early access.

Share Fast Facts

Delayed diagnosis of newborn hearing loss can dramatically impact speech and language development. Click to Tweet

“Most parents choose not to do it under anesthesia, so the hearing loss may go undiagnosed until the child is able to do a regular hearing test at age 4,” says Walsh. “That really delays diagnosis for unilateral one-sided hearing loss.”

Another benefit of the clinic? Less maternal stress, notes DeSell. “You have a newborn baby who fails the newborn hearing screen, and you’re anxious about whether your baby is deaf,” she says. “We try to get them in sooner so they’re not worrying about it.”

For more information about the clinic — one of only a handful in the mid-Atlantic region offering a complete range of specialized hearing tests for children — visit iHeardd.