Endoscopic treatment of Barrett’s esophagus involves destroying the dysplastic precancerous cells to prevent progression to esophageal cancer. In most treatment centers, that means using radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

But Mimi Canto and her therapeutic endoscopy colleagues in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Johns Hopkins are discovering new ways to attack even the most resistant cases of Barrett’s esophagus.

“Sometimes RFA doesn’t work,” Canto explains. “I have patients from around the country who have had multiple RFA treatments, and the Barrett’s mucosa recur. It’s possible that in some people, the tissue is resistant.”

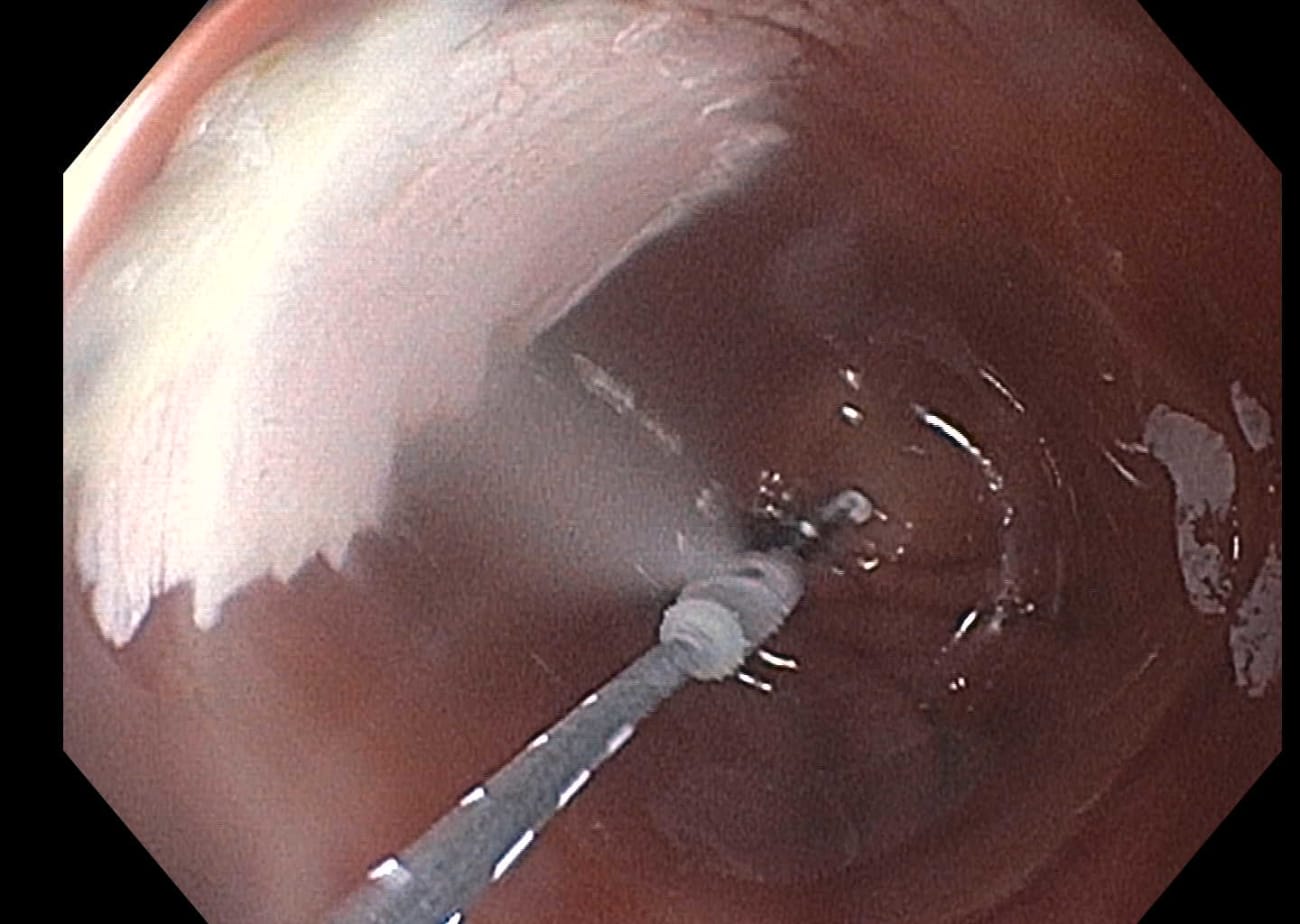

Canto is working on several multicenter clinical trials designed to learn more about using nitrous oxide cryoballoon ablation to treat Barrett’s esophagus. One such trial (Nitrous Oxide for Endoscopic Ablation of Refractory Barrett’s esophagus, or NO-FEAR trial clinicaltrials.gov NCT03554356) studies outcomes of cryotherapy for cases that haven’t responded well to the standard RFA treatment.

She says that endoscopic cryoablation - freezing the irregular cells, rather than burning them - can be a more effective treatment in patients for whom RFA hasn’t worked.

“We can usually do it in one or two [endoscopy] sessions,” says Canto. “The mechanism of cryo is quite different than burning.”

She uses a familiar household appliance to demonstrate an example.

“If you put a hot iron on your skin, it immediately kills the cells it touches,” she says. “All you have is a big burn. But cryoablation effects are very gradual, and result from multiple mechanisms.”

According to Canto, the whole process of cell destruction from cryotherapy can take as long as two weeks.

“First, it freezes the cells,” she explains. “Next, the frozen cells burst. Then, there is the vascular injury involving the tiny blood vessels, followed by ischemia, apoptosis and, ultimately, cell death.”

Cryobiology is a growing field in gastroenterology with much potential, says Canto.

“It’s been used for a while to treat solid tumors, like in kidney or liver cancer. It’s also used to treat atrial fibrillation.”

Among the multicenter clinical trial’s goals, she says, is to learn more about the benefits of cryoablation as rescue therapy for resistant Barrett’s esophagus.

For instance, she and her colleagues wonder if cryotherapy could replace RFA altogether.

“We want to know whether cryotherapy is a good first treatment or if we should save it for times when RFA isn’t effective,” says Canto.

Learn more about other research and clinical trials at bit.ly/HeartburnCenter.

To refer a patient to the Johns Hopkins Heartburn Center, email heartburn@jhmi.edu.