When Nicholas Zachos studies diarrheal diseases, he now looks at models of real, human intestine, cultured right in his lab. But that wasn't always the case.

Rotavirus and bacterial infections like cholera and enterohemmoragic E. coli continue to cost hundreds of thousands of lives each year around the world. Zachos says the medications designed to combat those infections are limited by a missing piece of research: cell models that can tell how sodium is absorbed and how chloride is secreted in human intestinal cells.

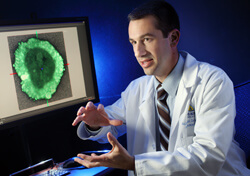

Applying new uses to groundbreaking discoveries of the Netherlands' Hans Clevers, Zachos and his team first harvested intestinal stem cells from mice and cultured them to grow in the lab. They then developed three-dimensional tissue structures-called enteroids-grown from healthy human samples.

But if there was to be real progress, Zachos says, they needed to study the real thing.

"We needed to know how water and ions are transported at the cellular level," Zachos says. "We wanted to know if we could actually mimic the real intestine. When we had cells that made up the epithelium, that was great. But we were still missing nerves, missing vasculature, missing the immune cells.

"Sure enough, through the enteroids, we could measure chloride secretion, sodium absorption and changes in intracellular pH-the things we needed to know. We could see these things changing the morphologies."

Zachos and his team also found that the enteroids have the machinery to replicate viruses and bacterial toxins, just as they replicate in the human body. "We're approaching this not just from an understanding of basic biology of the enteroids," he says, "but as a platform for drug development."

The enteroids also offer great promise in the treatment of injured or diseased colons.

"Take ulcerative colitis, for example," says Zachos. "We'd take a biopsy from a healthy area of intestine in a person who has ulcerative colitis, grow it in the lab, make a number of these three-dimensional structures. We can isolate them, put them back into the lumen of the injured colon and these things will find and fill in the damaged or injured areas."

After less than two years, Zachos and his team have assembled a bank of enteroids. Zachos says the original culture-of duodenal stem cells-was taken in the summer of 2012 and continues to replicate. "It behaves exactly the same today as it did when we first cultured it. It really speaks to the stability of the stem cell."