November 27, 2018

Recovering organs for transplantation is a race against time. Not everyone who needs a lifesaving organ can get one because of organ availability. Surgeons retrieving the organs can have less than six hours to safely remove them from a donor, determine whether they’re viable and transplant them into a recipient in need.

This is why some transplant teams at Johns Hopkins have been exploring ex vivo machine perfusion as a means to expand the donor pool, increase the range of donor hospitals and gain extra time to determine an organ’s health and performance before a transplant.

PROTECT Trial for Liver Transplants

In an international trial called PROTECT (Preserving and Assessing Donor Livers for Transplantation), the liver transplant team, led by principal investigator Shane Ottmann, has been comparing standard procurement efforts to procurement using a portable device containing a transparent, sterile chamber that stores a donor liver close to body temperature and pumps warm blood through it from the time of removal until transplantation. It can maintain the organ for up to 10 hours, allowing more time for transportation, assessment or possible pretreatment before transplantation.

Since July 2018, four patients enrolled in the trial at Johns Hopkins have received transplants, says liver transplant surgeon Russell Wesson. Two received a liver transported in the device and two received a liver through traditional procurement. All patients are doing very well, he says.

“Sometimes we decline to use livers because of concerns that they’re too far away, with resulting long cold ischemic times,” Wesson says. “This is a very exciting technology that could potentially expand the pool of good livers that can be used with very good results.”

EXPAND Trial for Lung Transplants

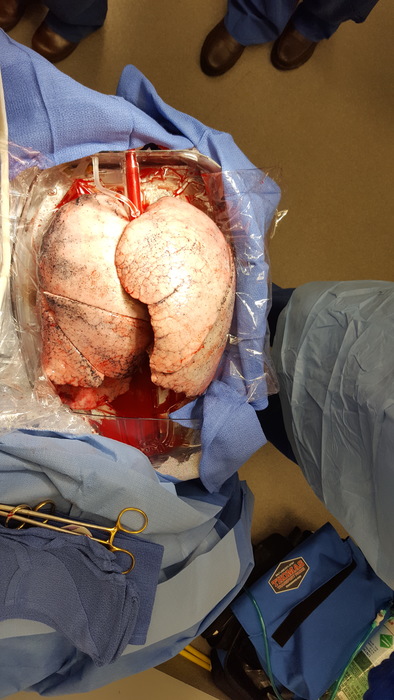

The lung transplant team also has been testing the device in a series of international, multicenter clinical trials called EXPAND (to expand the donor pool for lungs, where only 20 percent of organs are usable).The goal is to take the 80 percent of donor lungs not being used, put them on the device to give them time to recover and then transplant them if their function improves enough to meet the usual transplantation criteria, says Errol Bush, surgical director of the Advanced Lung Disease and Lung Transplant Program.

In the ongoing EXPAND II trial, which started in 2018, Bush has successfully transplanted lungs transported in the device into three patients. “Each patient had a successful transplant with an organ that would not have been utilized without the benefit of ex vivo machine perfusion,” he says. The first patient to have an organ transplant via ex vivo machine perfusion at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, a woman in her 30s with sarcoidosis and pulmonary hypertension, spent a typical 11 days in the hospital.

A previous study of the device, published in early 2018 in The Lancet, found a significant reduction in grade 3 primary graft dysfunction over traditional organ procurement efforts. The results of this trial led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to approve the device as standard of care.

“The technology is very promising,” Bush says. “We hope it will improve outcomes for patients and increase the donor supply, minimizing time on the waitlist.” If the device can safely store the organs for several hours, some transplant operations now performed in the wee hours of the night potentially could be postponed to standard operating room hours.